Jiab Prachakul (b 1979, Thailand) first came to attention in 2020 by winning the BP Portrait Award (Asian Art Newspaper, June 2020). She had first applied in 2017, but was not being shortlisted, however, the artist did what she always does: she took her faith into her own hands, pursuing her quest towards becoming a skilled and recognised artist, regardless that she had no academic training in art and belonged to the Asian diaspora in Europe with no contacts or leads in the art world.

Depicting family and friends from the Asian diaspora, her paintings explore Asian identity, but most of all address situations that are common to all of us as human beings. Fascinated by the medium of painting, Jiab Prachakul is an enthusiastic observer, curious and keen to learn from the likes of David Hockney or Lucian Freud in order to make portraiture a medium to be embraced by today’s generation whilst presenting a fresh look for the medium. Coming from the world of journalism and film, she aims to create the perfect painting, where the composition, aesthetics, and the overall feel are equally compelling. In the interview below, Jiab Prachakul shares her view on her trajectory and provides an insight into what it means to be a self-taught artist today.

Asian Art Newspaper: In the past, you were based in Berlin, London, and Lyon. Where are you living now?

Jiab Prachakul: I am presently living in Brittany, more specifically in Vannes, France. Before that, I was based in Lyon, but since I have asthma related problems, I decided with my husband to avoid a big city and move to a place which would have a positive impact on my health. We came here in 2021 and we very much love the lifestyle.

AAN: It is refreshing to see that someone that is not a graduate from a traditional art school can still make it into the art world. If you had to do it again, would you follow the same path or, on the contrary, choose the traditional curriculum?

JP: I appreciate not having a lot of training, not feeling the pressure of being in that kind of society where you think so much of yourself. It has been my experience that within the circle of artists, we sometimes think too much of ourselves and of our own practice. Of course, there are collective ideas between artists, but then I always valued that I studied journalism and filmography, because this gave me a wider perspective of life. If I could go back, I would do the years in Berlin differently. I had moved to Berlin from London because I wanted to become an artist. However, the years in Berlin proved to be most particular and very tough. In order to make a living there – without speaking German – I created my own business selling products based on my artwork. It was very successful in the local market and I lived off these sales. However, I did not have much time to do what I actually wanted to do, which was art. Therefore, if I was given the chance, I would certainly fix these eight years in Berlin, because I lost time and was not properly focused on what I really wanted to do.

AAN: Is fashion something you may pick up again in the future?

JP: I truly like fashion and, in my practice, I also love when my sitters care about the way they dress. Throughout their lives, in a span of 15 to 20 years, there are people whose style keeps changing with fashion, but for others, although their style developed with fashion, the core of their being is still the same. And that is precisely the aspect that interests me about fashion, not just the trend, but the character of the person and how they express this through the way they dress why they pick what they wear. However, I am not a fashion designer, I like to stay in the craft of making paintings, but overall I like to see and look at things, with an equal passion for fashion, film and cinema.

AAN: As much as there are numerous positive aspects in attending art school, sometimes it can also represent a burden or a constraint. As a result, some artists keep saying that it is essential to forget everything they learned at art school, when starting out. In your case, was your approach to move forward no matter what, regardless of what could restrain your creativity?

JP: I think I was the lucky one. Schools sometimes teach a different approach. Some artists would say that they were trained at school not to use the colour black out of the tube. On the contrary, I kept thinking why not use black paint out of the tube? Some years ago, the way I was working on my painting intrigued one of my friends, who had attended art school in Italy where they teach traditional classical painting. She was surprised that I used black concentrated black – and was wondering how I proceeded with its use? She could not imagine that I had simply used black colour from a tube. I can understand why this is being taught, but I also think that with these kind of rules and restrictions, you can end up losing some possibilities.

AAN: As an artist, getting gallery representation is a challenge, even more so as a self-taught artist. What hurdles did you face trying to get your foot in the door?

JP: In Berlin and London, I had been trying to participate in exhibitions – I found London a little bit easier, as my type of work, portraiture and figurative, was more accepted there.

In London, over the course of those two years, I felt it was easier to progress. There were different opportunities, for example, at a small local gallery or a festival to something like the BP Portrait Award, which is open to everyone. This is just so nice. In Berlin, it was another story. My type of art is not considered so cool and is not on-trend at all. When I sent my work to galleries, they would answer that they did not accept any unsolicited material. Basically, the message was quite simple: if you are not recommended by a curator or someone important, do not send any material as we have already too many artists. To them, the artwork seemed like it was adding to a mountain of rubbish and in no way did I want to be part of it. But then, looking back after being rejected by galleries, and as an artist with no training, perhaps my work was not strong enough. Of course, I draw and paint well, but then what do I have more than other artists who also paint well? The time in Berlin helped me realise why I paint what I paint, and what I want to say. Everyone has something to say: as a journalist, when you write, why would you want to write about a particular topic? The same applies to painters: why do you want to paint that, and why would a gallery want to support your idea? That is when I understood that it is not all about the fact that you are not in the art circle, or not from an art school, but it is primarily about your work. If your work is good, over time, it will speak for itself. When I applied for the BP award, I never thought of myself as a possible winner. In addition, when I look at the past winners, it is just so epic, and there have been ‘classic’ winners. My work is classic, too, but also my sitters are somehow out of context since they are all Asians. I came to realise that you need a little bit of recognition because it makes sense, similarly to when you rent a house, you need a guarantee. In Germany, for housing, you even need to prove that you do not have a bad background. For artists, it is the same thing, as you have the recognition from an institution or a place to say you are legitimate. As a result, everyone feels safer when it comes to investing in you and to collaborate with you because you are solid. As an artist outside of this, you are just constantly trying to fight to get to a place that can make you legitimate.

AAN: Your trajectory makes it obvious that there should actually be a prize for mid-career artists. Prizes tend to be limited age wise, and these days, it is not uncommon for artists to have had a career in another field before becoming full-time artists. Do you agree?

JP: You are absolutely right. Actually, I think about this a lot, because I keep looking at prize applications all the time, but it is so limited, even more so for figurative painting. Then, there is the age criteria and the country of origin. That narrows it down from the start. I am now 42 years old, and I end up being legitimate only for the Lee Krasner Prize and perhaps the Luxembourg Art Prize. For some of the other prizes, it is now too late, since I am over the age limit of 40, and beyond that, there is nearly nothing. In France, there are a few more options, but then, it is on another level.

So, absolutely, we should have that kind of prize, one that is also recognised by institutions, as you mentioned earlier, for people who could not start their art career before. That also applies to people from art school: how can they make a living for 12 years? It seems there are two choices: either you make it so big, or you are so poor. It is a career where people think you do not have enough credit if you do not make it to the top. Alternatively, if you try to make a living off your art work in a commercial way, you are automatically put in the artisan box, which for some artists can be a trap. Although that dichotomy exists in other careers as well, I find it is just more brutal in the art world. It is even more hurtful for vulnerable art students coming out of school, wondering what they are going to do for the next four years before they can make it. And we need to keep in mind that not everyone can make it to the top.

AAN: You applied several times to the BP award, which you won in 2020. Looking back, was there a difference of style or also of quality in your work?

JP: It was probably a combination of everything. I kept thinking I was going to keep applying until I would get in. One criterion of the BP award is always the same: the painting needs to convey the empathy of the sitter. That year, I did not produce that many paintings. Then, going over my works, Night Talk was the only one that fitted the description so I applied with that work. I never imagined that I would win the award, getting this recognition in such a legacy. Although it seems I covered all the criteria in the eyes of all the judges, it was also sheer luck as well.

AAN: It is interesting that you picked painting and portrait, the most ancient and traditional art form, which also makes it the most challenging to innovate. What can you bring to the medium that would be different or an addition?

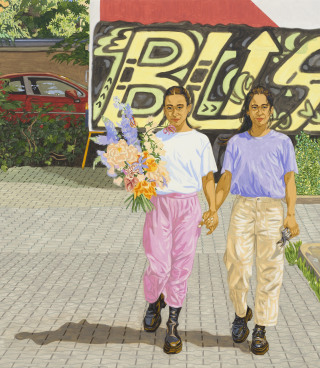

JP: Portraiture is wonderful subject matter, but it has been suffering from this ancient legacy, especially in Western art from Italy or France, where portraiture was usually just about and for the elite and aristocracy. My approach is the opposite, as I want to talk about ordinary people using my own lens. My sitter does not have to be someone famous or rich, but rather someone who has something special about them. In my painting, I expand in their life. When I do this, I feel the interconnection between them and me. For example, I have these sitters in Berlin, German- Japanese twins, whom I saw every weekend when I was working at the market. They were waitressing at Ramen House, where I used to go after finishing work. At the time, they were young, maybe 16 years old, and I kept wondering how come that although they are Asian, they move with such confidence? Over time, I learned that they were German, but when I see the expansion and the context of their life, I can find an interconnection; this is what I find interesting about involving with your sitters. Then, that specific context can come out in the portrait in the form of something we all feel the same way about, where we can understand the aesthetics and the sensation without class barriers.

Twelve years ago, when I decided to paint figures, I went to Florence and studied the beautiful early portraiture. I was simply stunned, and could not breathe. Looking at these portraits that represent the golden age of portraiture, I kept wondering how do you bring it back to our generation? Of course, there are artists like Lucian Freud (1922-2011), or especially David Hockney (b 1937), who focused on the figurative without being afraid to show what people really look like.

Portraiture has not been considered popular for a long time, but things seem to be changing. Artists like Kerry James Marshall (b 1955) brought back the wave of identity and being, with his powerful works. The first time I saw his work, I thought that was the rebirth of portraiture, because it is new, fresh, and has not been done. In the past, I cannot think of any reference in portraiture – Asian or French – between the impressionists and now. In my opinion, there was a big gap which has been filled by cinema with directors such as Truffaut, Godard or Rohmer depicting the aesthetics of people. Perhaps, this is a time where I can have painting and portraiture bridge the gap between cinema, photography, and classical portraiture? Maybe I can continue to work on something that is still an old format, but combine all these sensations together?

AAN: Do you have close relationships with your sitters? Do they actually sit for you, or do you paint from photographs? What is the process?

JP: I know all the people I paint in person. Maybe there is one commission where I have not met the person in real life, but we have known each other by talking on the phone or having common friends. I always need a connection between me and the sitters in order to feel honest about what I do, because if there is one thing I want to avoid in my work, it is to feel pretentious and create something fake. On Instagram, which I do not use anymore, I see so much fake content, it is everywhere. Therefore, I now try to figure out what is real and what is not. When I do things, I want to show what is real, what is honest, what is not pretentious and not just there to be seen.

My process starts in a more classical way. Before working on the actual painting, I meet the sitter. They sit for me in the studio, I take a photograph, and do a light drawing. I am not a fast drawer so I can only do one drawing. However, I realised over time that this process did not fit my approach. Therefore, I focus more on the sitting session, where I am not drawing or painting, but asking them some questions, interviewing them, talking to them about their childhood, and then taking the photograph.

Sometimes, taking photographs can be challenging because some people have a hard time losing the stiffness, or awkwardness, from their body and I end up taking close to 100 shots. Basically, I am not aiming at the best shot, I just need to shoot many and pick the right one. Sometimes, out of 200 photos, I would select a single one. If I do not exactly find the right one, I photoshop some parts together. Recently, the process has gone even further. Sometimes, I would create the scenario I envisioned or that I had experienced before. All too often, I would witness a great scene on the street that touched me, but would be too late to photograph it. Since I could not take a picture or memorise it, I would reproduce it by what I remembered, with the feeling of it, recreating it and then take a picture of it. I send it over to my sitters and their friends, for them to interpret it in their way, and see how they feel about it. They then take a picture of it and send it back to me. That is the latest method I have used and I find it to be so refreshing with the input and interacting of other perspectives.

This whole process is quite long, as I reflect on what I want to do, what kind of picture I want to produce and what I want to paint. Then I need to find the reference material, the sitters, the composition and ultimately, when it comes to the final stage, I can start working on the canvas. That is the moment when it is more about painting per se, about technical patterns, about painting skills, about what I want to explore by bringing all these processes together.

AAN: So it is a true collaboration between the painter and the sitter with the photograph going back and forth. You seem to establish a true connection with your sitter.

JP: I put a lot into the canvas as the sitters share a great deal about their life with me. Most of my sitters are my friends, family, and people I am close to and ultimately, the painting is an extension of me knowing them. For some of my friends, I keep painting them for a longer period of time, sometimes up to two years, even though within those two years they may change their state of mind, they have grown visibly older or their body has changed. Basically, it is a continual process of getting to know one another. We never stop growing and changing. In addition, I really like that I can keep interacting with them over time in this way.

AAN: For people you have known for some time, what features do you want to highlight? Is it a challenge to decide on the feeling, or character, of the painting?

JP: When considering the feeling I want to create in the painting is where I think my ego comes in. I feel, most of the time, every painting I did ultimately not just come from the character of the sitters. They may be different from me, but I always try to find a moment and a way to connect, so I can sympathise with them. Many things need to come together: the character, the moment, and the overall feeling, which is actually why I can totally pour my heart into the work. It comes down to me being them, and them being me – we truly coexist. Also, I like existentialism as a philosophy, and therefore, I feel that my existence as a person is not totally mine. It is a fractional part of many identities coming together, which I take from everyone around me. For example, if you look at the artist that I admire so much, and I want to take the path and become like them, then, their identity becomes mine. It goes back to the idea of archetype as well, all that is yours is actually not entirely yours, but it is just a fragment of others. I find this to be quite wonderful. When I meet my sitter in view of the painting, I am trying to figure out what it is in my sitter that makes me feel so proud to be me, what makes me feel comfortable to be a person, not just as an Asian person, but as a human being.

AAN: The diaspora is a topic you briefly addressed earlier with the example of the German-Japanese twins. You indicated you were struck by the confidence with which they were able to move in the world. Where does this level of confidence come from?

JP: When you see the Asian diaspora in a European context, you feel there is a little bit of holding back, or a little less confidence, because we are not in our own homeland or using our home language. Apart from all that, even if you speak the language, your appearance is just different and even if you were totally integrated in society, there would be someone or something making you hold back.

Somehow, these girls did not have this so much, and one of them said that she may not look like it, but she felt and was totally German. She thinks in a German way, lives her life the German way, and completely is at home. My experience is that I feel Asian, I am from Thailand, I have a Thai identity that is part of me, but then, my European part has developed considerably, outgrowing my Thai part. I think the difference between the twins and me is that I have the baggage of memories from Asia, the lifestyle, family, friends, as well as identities that are still so much embedded in me. However, I have another part that has now developed that has outgrown them, and both are constantly clashing. You always have to find a place where they can live together in a balanced way. In my opinion, that is the difference between diaspora that just moved to the country and a diaspora that grew up in the country.

Take my example, it took me 16 or 17 years to now live the life I had in Thailand at the same level I had back home in my birth country. I feel I have a certain comfort now, and finally, I can work in the career that I like and I can get involved with the people at the level that I had when I was in Thailand. There, I worked in advertising production companies, and my colleagues were always people in film, cinema, or advertising, remaining within the same kind of circle. Then, when I moved to London, everything was just torn apart, and I had to start from scratch: you cannot choose who you are going to be paired with or choose who you are going to go out with. If you are from Asia, or more specifically from Thailand, and this other person comes from Asia (or Thailand) too, you should be paired together and there is no way around it. However, companionship and friendship is not just based on coming from the same country, or even looking alike. It is also a matter of compatibility, and for me, that was actually one of the hardest parts. As a person from the diaspora living abroad, I felt that you could not choose. Ultimately, if you settle in one place, people start to know you in the stores, and you begin to feel that you are part of the community, that you belong somewhere. This is the way I have just started to feel recently. Adjusting to a new life is a very complicated process.

AAN: As to the backgrounds depicted in the paintings, are they real, staged, or invented?

JP: Most of them are real. As we discussed earlier, the paintings have to feel authentic. If I place my sitters somewhere where they do not belong, or there is no connection to them, then it is fake and not legitimate. Most of the time, I use a real background, trying to create the composition according to the proportions I envision. That approach has freed my practice a lot. Also, with real backgrounds, it is exciting for me to go into the details, connecting even more with the place and its objects. Before starting work for my upcoming exhibition at Timothy Taylor in New York in the autumn, I was not convinced I could paint nature and landscape, but since I moved to Brittany, I see things differently. Surprisingly, the nature and landscape here remind me of my hometown. My hometown was next to a river and the place where I live now in Brittany is next to a gulf, where the sunsets remind me of Thailand. So, once again, it is about the interconnection, about making connecting back and when I feel this I believe it is right for me to do these paintings.

AAN: Years ago, when you were in London, you went to see a David Hockney exhibition and experienced a moment of revelation. One does not experience such moments very often in life. How did it happen and how did it change the course of your life?

JP: Beyond the way the exhibition was curated and set up, walking through the different rooms made me aware of what you can achieve the moment you dedicate yourself to something. David Hockney’s work is just so good, so beautiful, it gave me goosebumps. Also, what I admire about him is that he also paints something very true of himself without pretending, depicting his own world. When you see the people he paints, they look interesting and you want to know them. They are not fake, but real because that is their identity. Whether they are artists, writers, designers or something else, they are real and that is the kind of art I like. As I walked through the exhibition, I also saw his work once he had moved to Los Angeles. Thework had developed, had become looser, and one could feel that he had reached a different stage in his life. At the time, I did not know anything about the artist. It is only after I found out more about his life that I came to realise that the works said everything already. He is truly an artist who is open to life. If he wants to do works using an iPad, he just does it. He is willing to explore. On my side, I am still young with time to explore and experiment. Up until now, I fought these tendencies towards letting go, because I feel skill is something you need to master and refine first before becoming more fluid. To me, it is wonderful to see the example of a master like Hockney and learn from the way he explores. However, you cannot rush yourself. Everyone has their own pace, but there comes a moment when you feel reassured and can take risks to be more free. Even after all that time, I still look at books discussing his work. In a way, they have become study books or guidelines for me when skill-wise I need to solve problems in my paintings. Beyond David Hockney, I also admire the work of Peter Doig (b 1959), who has also been an inspiration. It is interesting that you used the word ‘revelation’, because I experienced it twice in my life. One was the David Hockney exhibition, and the second time surprisingly, was not in any exhibition, but when I discovered the work of Kerry James Marshall, Toyin Ojih Odutola (b 1985) and Jordan Casteel (b 1989): it was just an explosion and although it may sound dramatic, I felt like crying. Considering my work, I could previously not associate myself with any specific period in time. When you look at art history from Impressionism to Expressionism and the Vienna Secession, where all artists joined together, it is a fact that you need to ride with the wave, and share ideas. There was a time when I thought these days of sharing ideas were gone, but I discovered other artists, who had started something I think I could be part of. This second revelation made me feel alive again in my practice.

AAN: In your career, you have always taken a moment to pause before taking the next step. What would you like to explore next?

JP: I am looking forward to developing further and seeing the possibilities. I feel happy with my practice at the moment although there are some elements, technically, I would like to address in a different way. I want to be more free, basically less focused, and less of a perfectionist. Being a perfectionist in my practice may come from my Asian side, where I impose on myself so many restrictions. I end up being so obedient in my work, as well as in my skill, that I am now truly looking forward to letting go, exploring just a little bit more and seeing where it will take me. As to the subject matter and context, I also want to work a lot more with people who are close to me – friends and family. I like the idea of the sitter that appears frequently, similarly to the films I like where the directors tend to use the same actors all the time. The same applies to my sitters: I want them to exist throughout each and every stage of their life. I want to explore that even more. During Frieze London, I visited the booth that featured some of my paintings in a two person show. Although it was nice to see all these beautiful paintings, I would also like to further explore the element of interaction. I was asking myself, what else could I bring to the show? Rather than showing paintings coming out of the studio, what could I bring to the exhibition in order to make the experience even more worthwhile? What new element can I offer to the audience, in addition to just look at the paintings? This is an aspect I am currently exploring.

AAN: It seems the audiences are now more open minded towards looking and appreciating art from all parts of the world. Do you agree?

JP: When it comes to works created by Asian artists, it seems to me there is a gap in the representation. From my perspective, I feel somehow stuck and classified in the traditional or classic Asian art world, which to me seems generally a little holistic or religious. The impression I have is that if you are Asian, as an artist, you must do something that people think is ‘Asian’, which can stereotype you. However, in that sense, I am doing something Asian and I have an Asian representation – I am Asian. But then, the question is what is this type of Asian art? That is the question. I completely agree with you that the context has changed considerably in museums, institutions, and galleries and curators are also much more open to the new context of what Asia really is and the context of the art made by Asian artists. And that is truly wonderful.